The industry we work in is built on top of legacy code, and ephemeral trends. The day-to-day experience of most developers involves working within large legacy code bases, and while every so often everything changes, all that really means for most people is that there is yet another layer of legacy code laid down. At least, if that trend hangs around long enough.

Sometimes those trends are not technological, they’re cultural. Not what we do; but how. The Agile Manifesto came out of the first dotcom bubble. During the boom preceding the bust, speed was of the essence, and the vast amounts of ancillary documentation and planning demanded by previous methodologies was just impractical. When you needed to deliver shippable results within weeks, rather than months, or years, things had to be done differently. The manifesto and the cultural change it brought was a huge point of inflection for our industry.

While Agile is still around, it’s no longer as cultishly observed. We have inevitably salvaged things from it, but the details — the pillars, the obsession with the ceremonies — have, for the most part, gone away. That happened because almost inevitably Agile lived long enough to evolve into something that cared more about the processes around development, than the development itself. It became the very villain it was supposed to defeat.

But from the salvaged parts of Agile we have fundamental changes in the way things are done. Test-driven development and pair programming are now just best practice. It’s pretty much unthinkable to do anything else.

I think it’s obvious to anyone in the industry that we’re reaching another one of those points of inflection, but this time around we’ll see both technological and cultural change. Because this time the cultural change is being driven by technological change rather than macro-economic changes happening in the background; it’s being driven by the arrival of large language models.

Just over a year ago now Jeremy Howard said something that at the time might have seemed controversial. Increasingly, documentation was for models to read, not humans. A year on, that statement is a lot less controversial; and there is now something new in the world, something that I’ve started to call documentation-first programming. Now you start at the prompt, rather than in the editor. At Warp, for instance they have very much started to eat their own dog food. As a company they have now mandated that every task should be started with a prompt. It doesn’t have to finish with a prompt, but has to start with one.

A couple of years back I gave a keynote where I talked about how large language models have at least started to appear to hold a model of the world; to be able to reason about how things should happen out here in the physical world. Now, that’s not really what is happening. They aren’t physical models, or at least the models we’re used to aren’t. Instead, they’re story models. The physics they deal with isn’t necessarily the physics of the real world, instead it’s story-world — and semiotic physics. They’re tools of narrative and rhetoric. Not necessarily logic. We can tell this from the lies they tell, the invented facts, and their stubbornness in sticking with them.

I argued that if prompt engineering was to become an important skill, it might not be the developers and software engineers who turn out to be the ones that are good at it: instead, it could be the poets and the storytellers who fill the new niche, not the computer scientists.

Although, if the recent launch of a specification-driven development kit by GitHub is indicative, it is not going to be the poets and storytellers that triumph. Instead, it is the product managers.

The arrival of the large language model has democratised programming. Although programming is inherently a creative process, developers are not artists putting paint on canvas, and alongside being creators, they must also be engineers who build systems that have to work. That means designing for testability, applying test-driven development, and using empirical evidence to guide decisions.

Because of that you can see a general-purpose builder role emerging: a mashup of designer, developer, and product managers, and inevitably it will be startups the lead the way. Because the point where people working at a startup have to choose a direction — rather than being a generalist, a builder — will stretch out. I think we can expect twenty- or thirty-person companies that are still full of generalists.

But prompt-engineering as skill is an artefact of the platform problem we see today with the software we have wrapped around our models. The new LLMs are tools that we’re not quite sure how to use, so they have been exposed directly to end-users in the most raw form. The hallucinations we commonly see when using LLMs are inherent, but the reason we’re seeing them is that the models are not properly constrained. The biggest platform problem we have when it comes to models is that we don’t have a universal abstraction of what a platform for machine-learning models should do. But what it certainly shouldn’t do is to let end users hack directly on the model itself; that way lie hallucinations and prompt-injection attacks.

Instead the interesting use cases for models is to solve problems, and most good companies have a lot of these. When it comes down to use cases, large language models are only useful where they provide the last missing piece in a technology stack that can already get ninety percent of the way towards a solution.

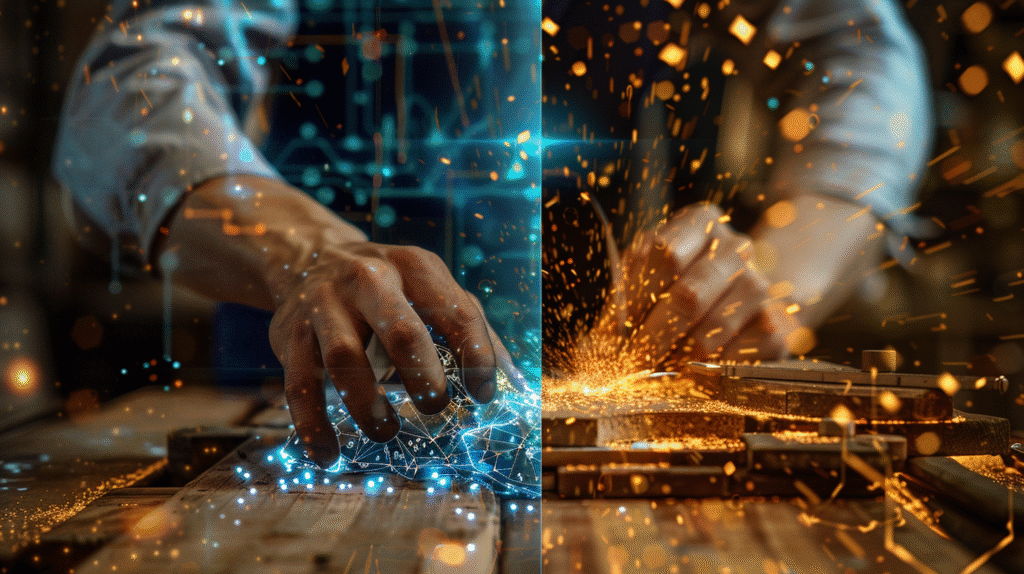

If you can build an minimum viable product in a month using AI, so can anyone else. We may we have reached the point where software isn’t interesting any more. We may well have reached the limits of pure-software business models, with the next wave of innovation coming from companies that vertically integrate across the entire stack to solve complex physical problems.

I’d argue that the next era of innovation won’t belong to the fastest, cheapest, or most scalable company. It will belong to the most obsessive. The most irrational. And dare I say, the most human. It will belong to the storytellers and the creatives.

Jony Ive tells an anecdote about the creation of the iPhone charging cable, and how his design team obsessed over how the charging cable was managed inside the box. He knew that millions of people would interact with both the packaging and the cable, making it a critical part of their first experience with the product.

When someone opens that Apple box, pulls out the cable, and notices the way it’s designed, something primal happens. That moment? It’s not the packaging, its not the design, it’s about care. The real battleground is no longer what you make, it’s how you make people feel. It’s about narrative.

This is the part no one seems to be talking about, this is where AI won’t flatten the field; it will simply widen the gap between the mediocre and the excellent. The popular narrative is that the arrival of AI will make mediocre work the new normal. Instead I’d argue the opposite: it will (it should) annihilate mediocre work.

It will call the bluff on anyone who never gave a damn in the first place. But the irrational? The hand-crafted? The meticulously obsessed? They’re the designers, the builders, who will become more valuable than ever.

The survivors won’t be the ones with the best models. They’ll be the ones solving the actual problems.